mitecars.com

email: [email protected]

In the Beginning... Part 2. The Hobby Quickly Spread Across the Country

Prior to the open invitational California Championship Model Midget Race held in Fresno, CA on March 26, 1939, tether car racing was limited in its appeal to small groups of local area enthusiasts who typically staged weekend races at crudely built tracks in their home towns. But that milestone event instantly transformed tether car racing from a local phenomenon to one of regional interest. A combination of Dick Hulse’s organizational skills and excellent support from local merchants in the Fresno area resulted in a hugely successful event. And extensive coverage of the event by the Fresno Bee newspaper soon attracted national attention. Articles proclaiming Dick Hulse as the “first time winner of this historic event” and showing a photo of his Dennymite-powered Dooling racer, accompanied by the caption “Champion of California”, appeared not only in the Fresno Bee but were also picked up by the national wire services and news of the Fresno tether car race spread across the country.

Within a few days after the event, Hulse received a telephone call from New York City from a gentleman by the name of Dave Elman. Elman hosted a radio show called Hobby Lobby which was carried on the NBC network of radio stations across the country. The Hobby Lobby show featured ordinary people who were invited to appear on the program as advocates for their unusual hobbies. Elman told Hulse that he wanted to know more about the “tiny race cars” and asked if he could hear one run. Hulse obliged his caller by firing up the Dennymite engine so Elman could hear the roar of the engine over the phone. At the conclusion of their phone conversation, Elman asked Hulse if he could bring his race car to New York to be interviewed on the Hobby Lobby and also to actually run his car on Elman’s show.

Because of other commitments associated with his real estate business, Hulse was not able to make the trip to New York. In his place, however, Ray Snow agreed to appear on Hobby Lobby and would bring Hulse’s Dennymite powered Dooling race car with him. But when Snow arrived at the studio, he found that there was very little space to run the car and a 15 foot long cable was the maximum that the facilities would allow. Snow said that the studio was packed with nearly 30 people standing around the circle and the sound men held their microphones over the crowd to catch the sound of the car and the reactions of the spectators.

After a brief interview of Ray Snow and an explanation of what was about to happen, Elman told his radio audience: “And now you are going hear how these fascinating tiny cars sound on the race track.” With that, the car was started and the loud roar of the engine startled the crowd. As it began to whiz around the small track, men yelled and laughed and women began to scream. Snow described the scene as “…utter pandemonium. People tried to get out of the way of the car as it buzzed around the small track and the excitement was reaching a fever pitch.

“Suddenly, there was silence on the air. No sound was being broadcast and the studio staff were yelling to stop the car…and we did!”

It was soon discovered that the loud roar of the car combined with the noise of yelling and screaming people had been more than the microphones could handle and the sound system failed.

It took several minutes before calm could be restored to the studio, but by then the phones of the radio station were ringing off their hooks, every caller wanting to know what had happened.

The telephone company called to say that the entire switchboard for NBC headquarters was lit up like a Christmas tree with calls coming in from across the country. Callers wanted to know where they could get information about the “tiny race cars” as Dave Elman had described them.

Over the next few days, NBC received several thousand calls and letters requesting information about the hobby. One particular caller, who specifically asked to speak with Dave Elman, was a gentleman by the name of Charles Penn, who identified himself as the owner of Penn Publications which published several hobby magazines, including Model Craftsman magazine for which Penn was Editor and Publisher.

Following his conversation with Elman, Charles Penn traveled to Hollywood and contacted Dick Hulse, requesting that Hulse drive to Los Angeles to meet with him to discuss the role that Model Craftsman magazine might have in promoting the fledgling miniature car racing hobby. Following their meeting in Los Angeles, Hulse agreed to serve as the West Coast representative for Model Craftsman and would provide articles and photos of America’s newest hobby. Shortly afterward, Dick Hulse and his family moved to Los Angeles where he ran the West Coast office for Penn Publications and Model Craftsman magazine began publishing news about the hobby on a regular basis.

Both Hulse and Penn brought their own individual strengths to their newly formed “partnership”. Dick Hulse’s success as a tether car racer had earned him respect and credibility within the hobby, and he now enjoyed nation-wide “name recognition” as a result of the national exposure that both he and his race car had received on the Dave Elman radio show. He had also proven to be successful at establishing local area clubs and organizing regional races. On the other hand, Charles Penn, as publisher of a national magazine capable of providing extensive coverage of the hobby, was potentially the most influential person in the country in terms of his and his publication’s ability to promote and grow the hobby.

The collaboration between Hulse and Penn had an immediate positive effect on both Model Craftsman magazine and the model car racing hobby. The June 1939 issue of Model Craftsman magazine included only three pages of coverage of tether cars, devoted entirely to the results of the California Championship Model Midget Race held in Fresno on March 26. In addition, there were no paid advertisements for model race cars. The July 1939 issue had three paid advertisements for miniature race cars and over six pages of tether car racing coverage, including a letter to the editor from Dick Hulse in which he proposed the formation of a national organization of model racing car owners. Charles Penn’s editorial response to Hulse’s proposal was supportive and invited input from readers, offering the resources of the magazine to promote the growth of the hobby.

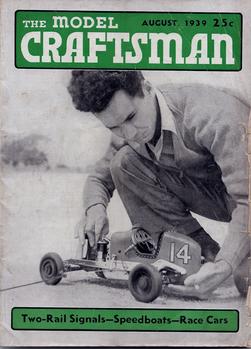

But it was the August 1939 issue of Model Craftsman which really began to bear the fruit of the Hulse-Penn relationship. Since its inception, Model Craftsman had become a publication which focused primarily on model railroading, but the cover of the August 1939 issue actually featured a gas powered miniature race car. And inside was a five-page article, penned by Dick Hulse, which included a preliminary outline for the formation of a national association of miniature racing car owners. The stated purpose of the proposed organization was to create a unified system of constructing and running model racing cars.

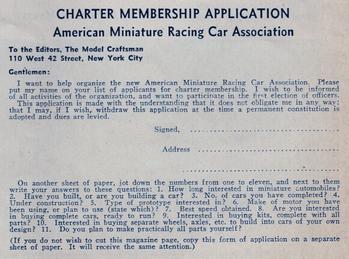

Readers were encouraged to mail in an application for charter membership in the proposed organization which was called the American Miniature Racing Car Association. Membership applications were to be sent to the editors of Model Craftsman magazine in New York City.

In his proposal Hulse noted that Model Craftsman would not dominate the proposed organization and that any information furnished by the publication should be construed only as an aid to the hobby. History would show, however, that while Model Craftsman may not have “dominated” the newly formed organization, the magazine did seek to influence its direction.

Charles Penn was well aware of Dick Hulse’s influence within the hobby and the roll that he could play in making both the miniature car racing hobby and Model Craftsman magazine successful. While Hulse was primarily a hobbyist who was motivated to help the hobby of miniature car racing grow and prosper, Penn was a businessman and he approached their relationship with less altruistic motives. His primary concern was increasing revenue from Model Craftsman by expanding his magazine’s readership and by increasing income from paid advertisements. Penn believed that by providing increased coverage of miniature car racing in Model Craftsman, his magazine would attract new participants into the hobby, and with them, new magazine subscriptions. At the same time, he felt that miniature race car and model engine manufacturers would recognize that Model Craftsman was the semi-official publication of miniature car racing and therefore they would seek exposure of their products via paid advertisements in his magazine.

Not surprisingly, the partnership of Hulse and Penn paid dividends. Through Hulse’s efforts, coverage of miniature car racing in Model Craftsman increased dramatically and interest in the

hobby began to spread. Clubs sprang up across the country and tracks were being built in scores of communities. Recognizing the growing interest in the hobby, a number of manufacturers of both miniature race cars and model engines sprang up almost overnight. Those manufacturers advertised their products in Model Craftsman and magazine sales increased. The hobby was growing and Model Craftsman was flourishing.

But the growth of the hobby was probably best described as being “out of control”. Manufacturers were producing race cars which varied widely in size and design; engine manufacturers were selling engines with differing physical sizes and a number of different displacements; and tracks were being constructed in various configurations with little or no regard for participants’ or spectators’ safety. Different clubs adopted differing sets of rules and regulations for both the conduct of their competitions and the design of the cars which would be allowed to compete. Often a car which was successful at one local-area track would not even be permitted to compete at another near-by track. Even when several clubs would agree to a uniform set of rules and regulations, thus permitting regional events, the lack of uniformity across the country negated the possibility of any national events.

So it was that Dick Hulse first proposed the formation of a national organization in a letter to the editor in the July 1939 issue of Model Craftsman magazine. His proposal immediately garnered the support of Charles Penn and subsequently attracted a positive response from a large number of readers as well. Model Craftsman noted that it was the outpouring of support from its readers which drove Hulse to formally propose the establishment of the American Miniature Racing Car Association in the August 1939 issue of Model Craftsman. Hulse noted that his preliminary outline for the national organization was a draft proposal submitted for readers’ review and comment.

The response to the basic framework which Hulse proposed was also favorable, and Hulse authored a draft of a proposed formal set of rules and regulations which were published in the February 1940 issue of Model Craftsman. But while Hulse’s “trial balloon” floated out in the August 1939 issue didn’t raise much controversy, such was certainly not the case with his more detailed formal proposal printed in the February 1940 issue.

Dick Hulse

Ray Snow

Dave Elman of NBC's Hobby Lobby radio program

Cover of August 1939 issue of Model Craftsman magazine

Charles Penn holding the Model Craftsman trophy.

Double click here to add text.

Application form for Charter Membership in AMRCA.

To continue this article...