mitecars.com

email: [email protected]

In the Beginning... Part 3. The Hobby Finally Became Organized

While the need for a national organization to provide some semblance of uniformity in governing the rapidly growing hobby of miniature car racing was never questioned, the publication of the proposed rules and regulations themselves stirred a fair amount of controversy. The basis for establishing the various racing classes, in particular, proved to be particularly troublesome for a number of individuals.

When first proposed in the August 1939 issue of Model Craftsman magazine, the preliminary outline which Dick Hulse drafted for the establishment of a “national model auto association” included a draft set of rules and regulations which stated that: “The motor shall be of internal combustion type and not more than 10 cc displacement (.62 cubic inches) and the car shall have a minimum weight of one pound for every 1/10th cubic inch displacement of the motor.”

This drew an immediate response from J. R. Forster of Forster Brothers whose Forster .99 engine would be ineligible for competition because of the .62 cid limitation. Forster proposed upping the displacement limit to 1.00 cubic inch.

Similarly, Mel Anderson complained that the rules unfairly discriminated against his .36 cid Baby Cyclone engine, feeling that even with the minimum weight requirements, his engine would not be competitive against the larger displacement engines. Anderson proposed the establishment of four different racing classes based on engine size; with Class 1 for .00 - .25 cid, Class 2 for .25 - .50 cid, Class 3 for .50 - .75 cid, and Class 4 for .75 – 1.00 cid engines. He also included a minimum weight requirement rule identical to that originally proposed by Hulse.

Recognizing the need to have the support of both hobbyists and manufacturers in establishing a national organization to govern the hobby, Hulse apparently took both Forster’s and Anderson’s concerns to heart. As a result, a formal proposal for the establishment of a set of “national racing car rules” published in the February 1940 issue of Model Craftsman magazine called for six different racing classes; five of which were based solely on engine size:

All of the engines in these five classes were required to be completely stock from the manufacturer with no modifications other than “porting” being allowed.

A sixth “Special Class” was reserved for modified or hand-built engines, regardless of displacement.

These classifications satisfied the concerns of the engine manufacturers and certainly discouraged both the modification of manufactured engines and the construction of one-off, hand-built engines, but it didn’t take long for the race car owners to voice their concerns. The March 1940 issue of Model Craftsman was filled with letters to the editor questioning the proposed rules, and subsequent issues of the magazine continued to include letters from racers across the country who took issue with the manner in which the different racing classes were established.

A racer from Fresno voiced his opposition to any engines larger than 0.61 cid. He also voiced his opposition to the requirement that engines be stock from the manufacturer, noting that few if any racers were currently running stock engines.

Walt Cave, another prominent member of the Fresno club, voiced his objection to engines larger than 10 cc (0.61 cid) and also to “lumping together” all modified engines, regardless of displacement, in the “Special Class”. He noted that hardly anyone was using an engine larger than those grouped together in “Class C”. He also went on to discuss why he felt that any attempt to limit the engines to strictly stock configuration would ultimately prove to be detrimental to the hobby.

Lyle Slaughter, the president of the Los Angeles-based Model Race Car Association, proposed establishing only two classes: one for engines of 0.00 to 0.36 cid and a second for engines of 0.361 to 0.625 cid, regardless of the level of modification.

The complaints weren’t limited to California racers. A prominent racer from Reading, PA, Cal Lieb, voiced his concern regarding the exclusion of any home-built parts on a manufacturer’s stock engine.

Finally, sensing that the growing controversy over the proposed rules could ultimately doom the establishment of a national organizing body, Charles Penn, the publisher of Model Craftsman magazine, hosted an informal dinner meeting in Los Angeles to which representatives of each of the West Coast race car clubs, and their wives, were invited. Interestingly, the list of invitees included most of the prominent miniature car racers on the West Coast but did not include engine manufacturers. Hulse, and to some extent Penn, had been accused of favoring the engine manufacturers in establishing the proposed racing classifications. As a result, the purpose of the get-together was to let hobbyists air their concerns with an eye toward coming to some agreement regarding the proposed rules and regulations. Based upon the success of that meeting, similar efforts were organized to gather input from other racing clubs and organizations across the country.

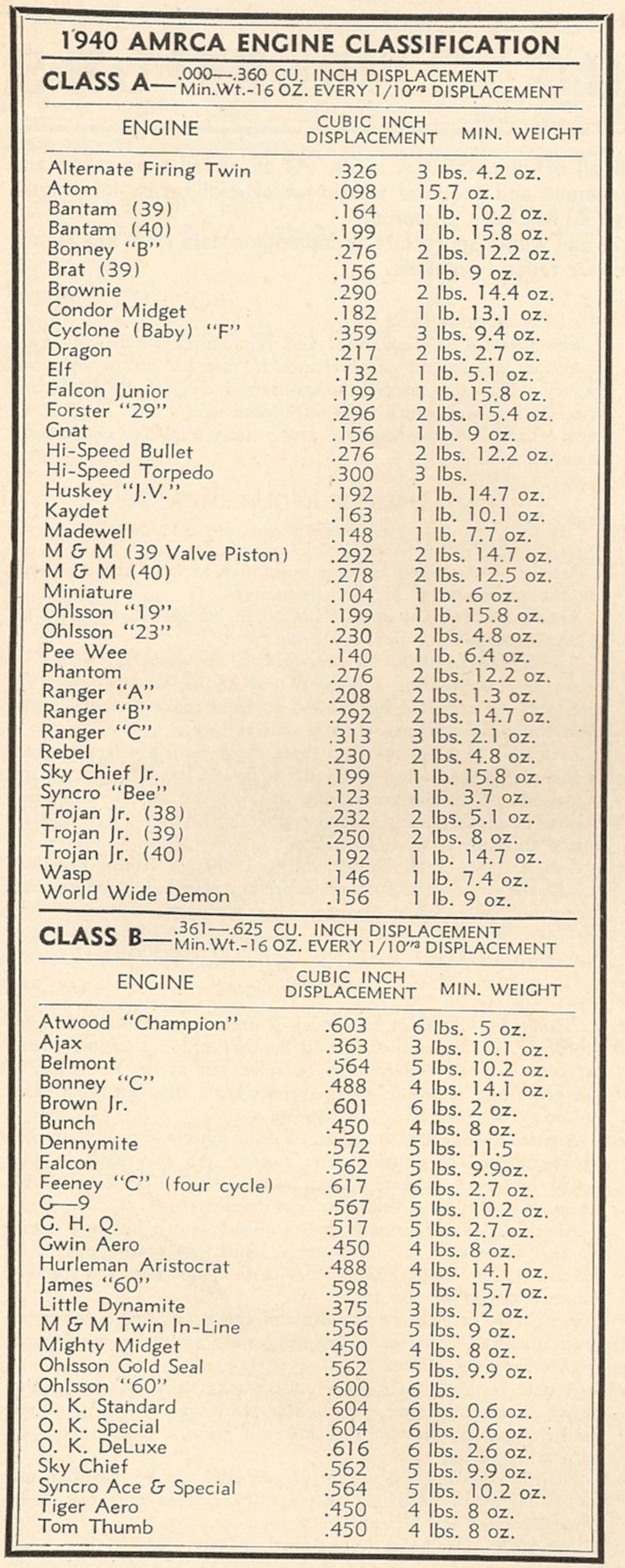

The final “revised racing car rules” were published in the June 1940 issue of Model Craftsman. Only two racing classes were specified: “Class A” for engine displacements of .000 to .360 cubic inches and “Class B” for .361 to .625 cubic inches. No restrictions on engine modifications were included. In addition, a minimum weight of 16 oz. for every 1/10th cubic inch of displacement was required.

Accompanying the rules was a tabular listing called the “1940 AMRCA Engine Classification” which included all of the known engines manufactured to date, along with their displacements, which were eligible for inclusion in each of the two classes plus the minimum weight required for each engine. Other engines were permitted, and their racing classes and minimum weight requirements were based upon their displacements.

Interestingly, after voicing their opposition to the initial rules proposal which provided for only a single racing class for engines of .62 cubic inch displacement or less, the responses of the Forster brothers and Mel Anderson to the final revised rules proposal were quite different. The Forsters continued producing their 0.99 cid engine for model aircraft use but did not develop a new engine aimed specifically at the “Class B” racing class. They did, however, produce smaller engines which saw limited use in the much less popular “Class A” racing class for engines up to .360 cid. Mel Anderson, however, developed a totally new engine, the Super Cyclone, specifically aimed at competing within the new rules. That engine soon came to dominate “Class B” miniature car racing.

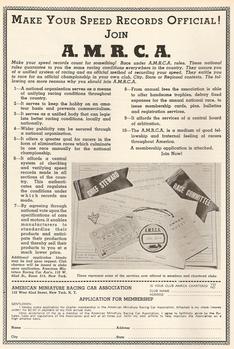

Following publication of the final “revised racing car rules” in the June 1940 issue of Model Craftsman magazine, the flurry of activity that had surrounded the establishment of the American Miniature Racing Car Association (AMRCA) and the controversy over its proposed rules and regulations appeared to be settling down. No articles or letters to the editor related to AMRCA were published in the next few issues of Model Craftsman, and it was only until the September and October 1940 issues that full-page advertisements encouraging readers to join AMRCA began appearing in print.

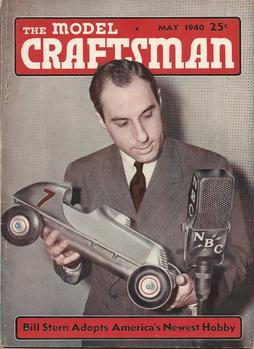

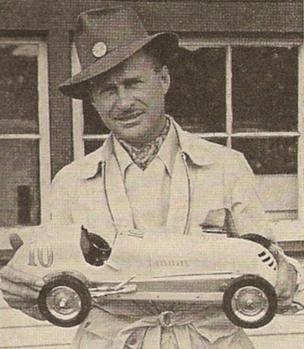

Meanwhile, the hobby continued to grow as new clubs were being established and new tracks were being built. A number of newly designed race cars were being introduced and new engines were being produced to power them. And a number of celebrities even jumped on the bandwagon, apparently seeking to cash in on the growing popularity of the hobby that was taking the country by storm. One of the country’s most widely recognized radio commentators and sportscasters of that era, Bill Stern, appeared on the cover of Model Craftsman magazine holding a Matthews Silver Streak race car. Not to be outdone, Stern’s boss, Major Lenox Lohr, the president of NBC, and his Holley Speed King race car were the subject of a feature article in the August 1940 issue of Model Craftsman. And in that same issue, Wilbur Shaw, three-time winner of the Indianapolis 500, was shown holding a B. B. Korn Indianapolis race car.

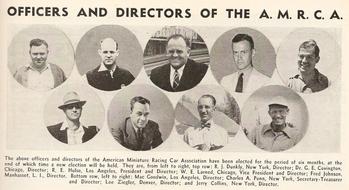

The next significant development related to the establishment of AMRCA appeared without fanfare in the November 1940 issue of Model Craftsman. A photo collage entitled “Officers and Directors of the A.M.R.C.A.” included the photos and names of nine individuals who formed the initial slate of officers of the newly formed organization. Included were Dick Hulse as President and Director, and Charles Penn, the publisher of Model Craftsman magazine, as Secretary-Treasurer and Director. The caption under the photos noted that the officers and directors had been elected for a period of six months, after which a new election would be held. The so-called election which resulted in the initial appointment of the nine officers and directors had not been announced and had received no publicity prior to the announcement of the names of the winners. It was not known who might have actually voted in this so-called election.

While the manner in which the officers and directors were elected was certainly open to question, the caliber of the individuals selected was not. Serving as President was Dick Hulse, whose active participation in promoting the hobby and whose leadership in establishing AMRCA were exemplary. In addition, his organizational and business skills made him well qualified to lead the fledgling organization. Charles Penn brought both his business acumen and the considerable influence of his publication to a board of directors whose primary responsibility was to continue the orderly growth of the hobby. And the remaining officers and directors were active and well respected racers from different geographical areas across the country, including representatives from New York, Chicago, Denver, and Los Angeles. While one might argue that no manufacturer’s representatives were included in the slate of officers and directors, no one could say that the grass roots racers weren’t well represented.

Early advertisement for AMRCA from Model Craftsman.

1940 AMRCA engine classifications and minimum weights.

Bill Stern on the cover of Model Craftsman magazine.

NBC President Lenox Lohr and his Holley Speed King car.

Indy 500 winner Wilbur Shaw and a B.B. Korn Indianapolis

car.