mitecars.com

email: [email protected]

Ridin' the Rails in Tyrone

The vast majority of gas powered miniature race cars were designed and built to race competitively on a single-lane, flat, circular tether track where one end of a cable was attached to the race car and the other end was attached to a post in the center of the track. Once the car was pushed off, centrifugal force kept the cable taut as the racer built up speed circling the track. The cars were timed individually and the competition was between the race car and the stop watch. Unfortunately, cable tracks allowed only one car to circle the track at a time.

A second type of race track permitted several cars to race against one another at one time. These tracks were called rail tracks and some hobbyists felt that the future of racing miniature race cars would ultimately lie with rail racing. Even though speeds were slower because of the greater frictional losses associated with rail tracks, the attraction of several screaming cars racing head-to-head was considerable, especially from a spectator’s perspective.

Rail tracks were typically oval-shaped with moderately banked straightaways and steeply banked turns at each end. Bankings of 50 to 60 degrees were not uncommon, and one circular track in California boasted 90-degree banking around the entire circumference of the track. Rail tracks were built of wood and featured either four or six lanes, depending upon the configuration of the track. A flanged steel rail flanked each lane and the cars were “locked” to these flanges by ball bearings mounted on studs attached to the left side of the car. Several prominent race car designers and builders developed rail track designs, including the Dooling brothers and Ray Snow of Hornet engine fame.

The Dooling brothers’ design was published in an article authored by Russell Dooling in the April 1940 issue of “Model Craftsman” magazine. The article included detailed drawings and was apparently based on Dooling’s experience with a rail track that he had built in the late 1930s. The four-rail track designed by Dooling covered an area 140 feet long and 80 feet wide and featured 55-degree banking on the turns, guide rails fabricated from 14-gauge mild steel in a 5/16 - 7/8 – 5/8 inch U-section, and a masonite racing surface.

Rail tracks were relatively expensive to build and, because of their wood construction, were subject to the ravages of weather. Nonetheless, rail racing was popular in a number of areas of the country, including California, Chicago, Milwaukee and Pennsylvania. But ultimately the cost of maintaining these facilities contributed to their demise.

One of the few rail tracks in the country which welcomed the smaller mite cars was the Tyrone Miniature Speedway located on the site of a ballast quarry about a mile and a half south of Tyrone, Pennsylvania on PA route 350. Construction of the track was promoted by Jack Vanneman, a Tyrone resident whose family owned the ballast quarry where the track was to be built and who served as president of the local Tyrone Miniature Racing Club, which was later renamed the Central Auto Racing Society (CARS). Actual construction of the track was accomplished as a class project by students enrolled in a carpentry class of the National Youth Administration. The National Youth Administration (NYA) was a New Deal agency in the United States which operated from 1935-1943 as part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The NYA served high school and college age youth who were paid to work on work-study projects through their schools as well as youth who came from relief families.

The Tyrone track was modeled after the Dooling brothers’ plans for a four-rail, 1/16th mile board track. The track hosted its first American Miniature Racing Car Association (AMRCA) sanctioned race on Labor Day in 1942. The track sat idle during World War II but reopened in 1946. By the end of the 1947 racing season, the popular rail track had become a little the worse for wear and slightly rough. As a result, an extensive renovation of the track was completed prior to the start of the 1948 racing season. A new tempered masonite racing surface was installed along with four new guide rails, a new crash fence and spectator guard rail, and new starting equipment. In addition, new work benches and spectator stands were constructed.

Interestingly, the Tyrone track resisted charging admission to its races until 1950, when an admission charge of 29 cents was implemented. Children were still admitted free but a 25 cent parking fee was also added. During its heyday, the Tyrone track would attract 1,500 to 2,000 spectators to its Sunday afternoon races.

Much of the success of the Tyrone track resulted from the efforts of Jack Vanneman in promoting interest in rail racing. Vanneman served as the eastern distributor of the Curly Glover-designed Curly Cars, which were very competitive .60-size rail racers of that era. One of Vanneman’s promotional efforts involved the establishment of a pool of used race cars and equipment. As club members replaced their cars with newer models, their old cars were made available to new members of the club at no cost. To be eligible for one of these older but still competitive cars, a new member had to meet certain qualifications, including evidence of character and genuine need for financial aid. A committee of club members reviewed each application and, if accepted, the car became the property of the new member. The only stipulation was that if the new member should buy a new car or drop out of the club, the old car reverted back to the pool. A number of used Curly Cars and Real McCoy mites which were modified for rail track racing found their way into the hands of new club members through this process.

Another of Vanneman’s efforts directed toward promoting the hobby was to schedule mite car racing on the Tyrone rail track on Thursday evenings during the 1950 racing season. Vanneman had hoped that the lower cost of mite cars would attract new participants who would eventually move up to racing the larger .60-size cars on Sunday afternoons. Toward this end, Vanneman modified the popular Real McCoy mite car by attaching a set of rail guides in place of the usual pan handle found on tethered versions of the car.

Vanneman kept one of the modified Real McCoy rail mites for his own use, painted in his familiar orange and black #2 livery. Several other Real McCoy cars which Vanneman modified for rail track racing were loaned to newcomers to the hobby in an effort to encourage them to begin racing with the smaller mite cars with the hope that they would then move up to the larger .60-size cars. As was the case with Vanneman's pool of used .60-size rail cars, the new owners were expected to return the modified Real McCoy cars to Vanneman if they either moved up to the .60-size class or simply dropped out of the hobby.

Unfortunately, the popularity of mite car racing on the Tyrone track did not meet Vanneman’s expectations. Only a handful of cars would turn out for the Thursday evening races and the experiment with mite cars was short-lived. The Tyrone track hosted its last formally sanctioned races in 1952. Vanneman blamed the growing popularity of a modern-day marvel, television, for the decline in interest in miniature car racing. A few local racers occasionally tried to run their cars on the track during the summer of 1953, but by then the weather had taken its toll on the track. The rails would often come loose and break the rail adaptors on the cars and the racing surface was quite rough.

The track was finally abandoned and left to deteriorate. Eventually a new highway was built through the site of the storied rail track.

________________________________________________________________________

The author wishes to thank Nathan Ewing for his assistance in researching the history of the Tyrone Miniature Speedway.

Tyrone Miniature Speedway in 1947.

Launching rail cars at Tyrone.

Jack Vanneman's personal rail cars...Real McCoy rail mite (left), "Short Tail" Curly Car (center), "Long Tail" Curly Car (right).

Vanneman's Real McCoy modified for rail track racing.

Section of rail from the Tyrone track shown with the car's rail guides positioned on the rail.

Custom ball-bearing front wheels, custom front axle, after-market fuel tank, and bolt-on rail adapter on Vanneman's Real McCoy which was modified for use on the Tyrone rail track.

Vanneman-modified Real McCoy with rail guides which was built for a newcomer to the hobby and raced on Thursday nights at the Tyrone rail track.

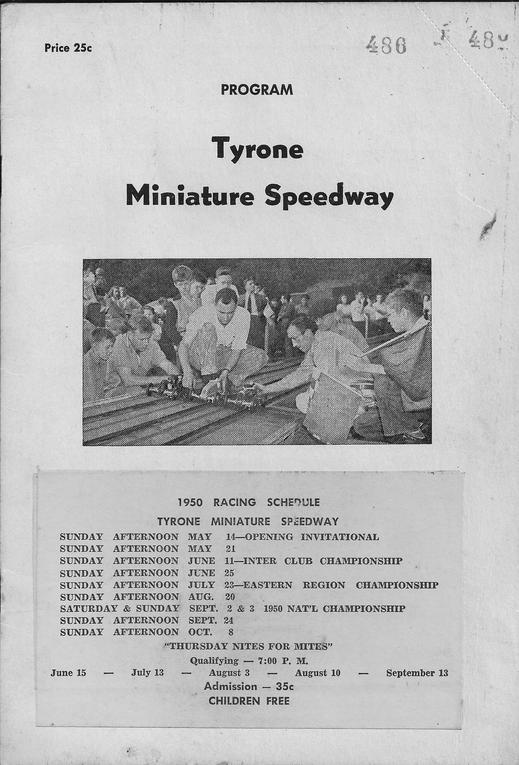

Front cover of 1950 program for Tyrone Miniature Speedway showing the "Thursday Nites for Mites" schedule.