mitecars.com

email: [email protected]

In the Beginning... Part 5. Charles Penn's Influence on Mite Cars

Model Craftsman Publishing Corp., originally headquartered in Chicago, was founded in 1933 by Emanuele Stieri. Stieri has been characterized as a prolific how-to writer, and he served as the first editor-in-chief of The Model Craftsman magazine. However, shortly after its establishment, the publishing company was sold to Charles A. Penn, who moved its headquarters to New York City in 1934. Penn served as editor and publisher of The Model Craftsman magazine throughout his tenure as owner of the parent company.

Under the direction of first Stieri and then Penn, The Model Craftsman covered a wide range of areas of scale modeling, including the hobby of building and racing gas powered miniature automobiles. The Model Craftsman magazine continued to be the authoritative publication for miniature car racing until Penn sought to cash in on the popularity of the hobby by establishing a new publication entitled Model Race Cars in May 1948. While Model Race Cars magazine limited its focus to the hobby of miniature car racing, The Model Craftsman continued its broad coverage of other areas of scale modeling until it eventually limited its content to model railroading starting in April 1949. The Model Craftsman magazine continues to be published today under the title Railroad Model Craftsman. Unfortunately, Model Race Cars magazine lasted only 16 issues, ceasing publication after its August 1949 issue.

Charles Penn retired from the publishing company in 1962 and passed away shortly afterward. But prior to his death, Penn had the distinction of being the only person in the United States to be the owner of an entire town. In 1949 Penn purchased the town of Bumble Bee, AZ with the intention of restoring the virtual ghost town and building a railroad museum. Penn’s vacant house in Bumble Bee is still standing, but his plans to restore the town and build a museum never materialized.

However, while Charles Penn was editor and publisher of The Model Craftsman, his influence on the miniature car racing hobby, especially during its infancy, was considerable. Penn’s introduction to miniature car racing came on the heels of Dave Elman’s “The Hobby Lobby Show” in which Dick Hulse’s race car was actually raced inside the studio during the live national broadcast of the program on NBC radio. Calls from listeners around the country flooded into the station, a fact which did not go unnoticed by Charles Penn. Sensing that this was an opportunity to get in on the ground floor of a new hobby with considerable growth potential, Penn contacted Elman at NBC headquarters in New York City and obtained the address and phone number of Dick Hulse. Recognizing that Hulse was highly regarded within the fledgling hobby, Penn arranged to meet with him in Hollywood to discuss what role The Model Craftsman magazine might have in helping to grow the hobby of miniature car racing.

By the end of their meeting, Penn had agreed to establish a West Coast office for Penn Publications (as the company was now known) and to begin publishing articles about miniature car racing in The Model Craftsman on a regular basis. In return, Hulse agreed to serve as the West Coast representative for The Model Craftsman magazine and to provide both articles and photos to support the growth of the hobby.

By partnering with Hulse, Penn became arguably the most influential person in the country in terms of his ability to influence the growth of the hobby. His magazine could provide the national exposure which the hobby needed, and Hulse’s name lent credibility to that effort.

But, while Hulse’s efforts directed toward growing the hobby were based primarily on his interest as a hobbyist and participant in miniature car racing, Penn’s motives were purely financial. Recognizing that miniature car racing had the potential to grow to include a large number of hobbyists, his reasons for assisting in the growth of the hobby were based on the potential to increase the readership of his magazine and to attract additional advertising revenue from manufacturers.

Penn’s and Hulse’s efforts were successful, as more and more hobbyists across the country began building and racing miniature automobiles. As a result, many new manufacturers started business to meet the demand for race cars, engines, and parts. And recognizing that The Model Craftsman was the predominant publication covering model car racing, the number of subscriptions to the magazine grew quickly during that era, and manufacturers increasingly purchased ad space to showcase their products. The hobby was growing and The Model Craftsman magazine was flourishing.

But, both Hulse and Penn sensed potential problems for the rapidly growing hobby, and while their rationales were totally different, both concluded that increased emphasis on the smaller “mite” cars was in the best long-term interest of the hobby.

Dick Hulse was concerned that the increasing speeds of the larger cars, typically powered by .60-size engines, were making them dangerous and that the races were becoming unsafe. His solution to this perceived problem was to reduce the size of the engines in an effort to slow the cars. And Hulse directed his efforts toward building a truly competitive mite car.

Penn, however, was concerned about the rising cost of the larger .60-size cars, believing that the cost of a competitive race car was often beyond the means of the average hobbyist, thus prohibiting youngsters and lower income adults from joining the hobby. Penn feared that if the cost of the hobby was more than they could afford, hobbyists would pursue other activities and would not subscribe to his magazine. Penn’s solution to this problem was to launch an effort to make race cars more affordable by promoting the use of smaller, less expensive engines (a stance which he supported through the editorial columns of his magazine) and by publishing several do-it-yourself articles for the construction of inexpensive home-built race cars.

The first of the smaller, home-built race cars was a 12 ½ inch long car called the Pegasus, which was featured in a pair of do-it-yourself articles in the April and May 1940 issues of The Model Craftsman magazine. The author of the articles, and the designer of the car, was identified as Larry Eisinger. Eisinger had previously contributed several articles on model airplanes to the magazine, and it appears that Penn enlisted Eisinger’s assistance in supporting his obsession with smaller, less expensive race cars. Eisinger’s efforts were apparently rewarded as he was named an associate editor of the publication shortly afterward.

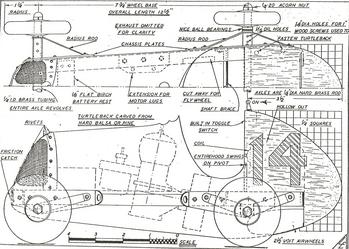

The Pegasus was designed to be powered by a .20 to .30 cubic inch spark ignition engine. Eisinger noted that the car required an outlay of less than $6.00 in materials, less the cost of the engine. Even after including the cost of a suitable engine, he cited a total cost of less than $15.00 to finish the car. The articles included working drawings which could easily be scaled to full size, a detailed bill of materials which even included the catalog number for the correct Boston gears, and step-by-step instructions in the text of the articles for completion of the car. Eisinger noted that the only tools which were required to complete the car were a hand drill, file, vise, hack saw, and a few threading tools and he implied that the car could be built by a rank amateur.

Even though the Pegasus was doubtless an inexpensive and fun car to build, it could hardly be considered to be a competitive race car. And in spite of the considerable efforts of both Penn and Hulse, this was not the direction in which the hobby was headed. The constant pursuit of speed, with faster race cars on larger and faster tracks, ran counter to their support of the smaller engined mite cars. The mighty .60s would soon rule the hobby.

A completed Pegasus car is shown in the accompanying photos. This example follows Eisinger’s articles closely, although the frame on this particular car was made of brass rather than aluminum. The hood and belly pan were fabricated from sheet steel and the nose features a tea strainer grille. Although the bill of materials in The Model Craftsman article called for the use of 2 ½ inch diameter Voit airwheels, Eisinger freely admitted that they were unsuitable for use on a race car. This particular example is equipped with 3 inch wheels and tires from a British Meccano construction kit, which was somewhat similar to the Gilbert Erector sets sold in the United States. This car is believed to have originated in Australia, and that might help to explain the use of the Meccano wheels and tires. The car is powered by a .29 cid 1940 Brownie Model E spark ignition engine.

Plans for building the Pegasus car.

Article from the April 1940 issue of Model Craftsman magazine which included plans and a bill of materials for the Pegasus car.

A completed Pegasus car equipped with Meccano wheels and tires, believed to have been originally built in Australia.

Pegasus car powered by a .29 cubic inch 1940 Brownie Model E spark ignition engine.